Algorithms that design structures better than engineers

A beam supported on the left hand edge, with downward force applied to the bottom right. The optimisation algorithm distributes the material in the way to minimise the deflection.

You are watching an optimisation algorithm come up with the stiffest design completely automatically.

The outcome is the stiffest shape possible for a given amount of material. Amazingly, it’s a nuanced truss that isn’t far removed from the look of most motorway bridges. That’s pretty reassuring, actually.

The name for this process is topology optimisation – essentially making the best use of shape for structures. Finding out the best way to use the least material is the goal of pretty much all structural engineering and optimisation and evolutionary algorithms represent a paradigm shift in this field.

By specifying the overall constraints and loading, the algorithm finds the optimal distribution to minimise or maximise your desired performance (deflection, compression, heat transfer… anything you can describe mathematically). The result is that can design parts that can support the same forces, yet use less than half of the original material.

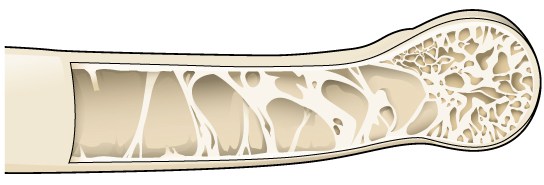

As another example, if I increase the resolution of the system, and reduce the constrain on minimum width of a strut, we get something that looks closer to the inside of a bird’s bone than anything man-made.

Here, starting with a 1200px x 600px grey beam, loaded in the centre, this automatically figures out where the best layout of the material is.

The inside of bird’s bone, which has been optimised over millions of years for optimal stiffness and lightness.

The technique of topology optimisation has been around for decades but the constraints of mass production and joining techniques has meant it was always impossible to produce these super stiff but oddly-shaped structures. Now, with the advent of 3D printing, these designs can be directly realised. The potential for this for ultra-performance parts in aerospace and mechanical engineering is staggering.

I’m investigating this technology for my masters project, particularly the compromises needed in manufacturing them with 3d printing. If you have any knowledge or suggestions in this area I’d love to hear from you (email or twitter).

This sample 2D image was made with ToPy – open source Python Topology Optimisation code.